Please heart, share, restack! Bimbo Summit is free as always. I deeply appreciate paid subscribers and so do you—they subsidize the paywalls I have to get behind to write this stuff 💋

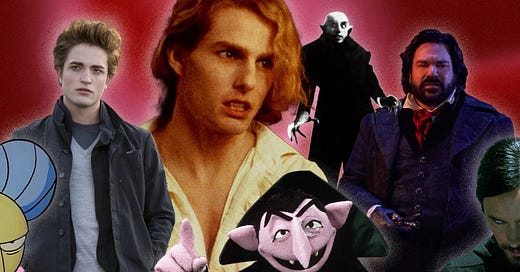

Remember that post I wrote about Nosferatu last year? If not, TL;DR: some people got mad that I dared to be critical of vampire legends. Nevertheless, I’m still critical! Here’s why.

Lately, I’ve been revisiting Stephen King’s On Writing. He speaks at length about having “IRs” (important readers) to point out plot holes in your writing. I’m not sure why this book is so lauded because his advice doesn’t transcend this level of common sense/workshop 101, but I digress. What struck me about his thoughts on plot holes wasn’t that I should get someone to point them out to me, but his research on just how common they are—and how frequently he himself has ones “big enough to drive a truck through.” Raymond Chandler, apparently, forgot an entire character existed once and the novel still got published.

Perhaps because this was on my mind, I started wondering if one of the oldest vampire tropes (the whole “they can’t enter your home without an invitation” thing) is actually a plot hole in…folklore, I guess. I mean, why can’t they cross? What stops them? And more importantly, what’s the narrative and cultural purpose behind this rule? Is it just a convenient plot device—much of vampire cinema would have very little conflict without it—or is there more to it?

Of course, this idea does indeed have deep roots in Eastern European folklore, particularly from Romania and Hungary. In these traditions, the home is seen as a sacred space, a sanctuary protected by certain rituals and beliefs. The threshold isn’t just a physical boundary; it’s a symbolic one, representing the line between the known and the unknown, the safe and the dangerous. Vampires are depicted as needing an invitation to enter a home in order to symbolize the sanctity and protection of one’s personal space.

Vampire lore in this instance breaks another one of King’s rules: never, ever let theme direct plot.

If we consider folklore as a form of cultural storytelling—a way societies pass down values and norms—then it’s fair to say that folklore can also serve as propaganda. For example, The Grimm Brothers’ broader motive was to preserve what they saw as Germany’s authentic folk heritage and use it to promote national unity . They even described their collection as an “educational tool,” hoping that widely-shared fairy tales would strengthen German identity – indeed, generations of German children grew up with the same beloved stories, instilling a shared national consciousness from an early age . In effect, the Grimms transformed folklore into a vehicle of cultural propaganda, deliberately reshaping old tales to reflect and reinforce the values of a proud, cohesive German nation. While not all fairy tales are so intentionally crafted to promote the state, they do tend to reinforce certain behaviors and beliefs, often to maintain the status quo.

I think a refusal to acknowledge this is exactly why Disney live action films are in their flop era. The production company has radically failed to see that the success of Maleficent was because it subverted the messaging of the original. If they want traditional morals, audiences will watch the cartoon version. That said—give us Sabrina Carpenter in Tangled NOW.

Anyway, my question is: when we tell stories where vampires need an invitation to enter, what are we really saying? That evil can’t touch us unless we let it in? That victims are complicit in their own victimization? This kind of messaging shifts the focus from the predator to the predated, implying that the onus is on individuals to protect themselves, and if they fail, well, maybe they were asking for it. (An incredible exploration of good takes place in Joyce Carol Oate’s short story “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been.” The story is based on a real serial killer, but my students very commonly believe this is a vampire tale.)

My second problem with this logic is that not everyone’s home is a sanctuary. For women in particular, the place that’s supposed to offer safety and comfort can be the most violent place in their lives. A recent report by UN Women found:

85,000 women and girls were killed intentionally by men in 2023, with 60% (51,100) of these deaths committed by someone close to the victim. The organisation said its figures showed that, globally, the most dangerous place for a woman to be was in her home, where the majority of women die at the hands of men.

There’s one caveat to these statistics—for Black women, home is relatively safer. Research from the Bureau of Justice Statistics and the CDC shows that Black women face disproportionately high rates of violence in public spaces, including assaults and homicides by strangers. Kimberlé Crenshaw and Angela Davis have argued that systemic racism, policing violence, and economic inequality create a double burden where Black women are at significant risk both inside and outside the home — but, usually, the outside world can be even more dangerous.

This shows up in Sinners, which is one of the many reasons why this film feels like such a breath of fresh air. Directed by Ryan Coogler and starring Michael B. Jordan, it’s a vampire movie that doesn’t just rehash old tropes—it interrogates them. In Sinners, vampires adhere to the traditional rule of needing an invitation to enter. However, the context is crucial: a Black community in 1930s Mississippi has gathered at a juke joint, which has been fortified by twins, Smoke and Stack (both played by Jordan). The brothers have secured their establishment not just against supernatural threats, but as a haven from the very real terror of the Ku Klux Klan. The invitation rule becomes a metaphor for the community’s vigilance and the sanctity of their hard-won safe space.

In a genre that’s become increasingly stale, Sinners stands out. It’s not just a good vampire movie; it’s a good movie, period. It respects the intelligence of its audience, asks difficult questions, and refuses to offer easy answers.

So, yeah, I’m over vampire movies—except for Sinners. And, no, I haven’t read Salem’ Lot and I don’t know how King handles the tropes that violate his craft rules, but if you do, drop it in the comments!

This is a great take! I just wrote a piece about how Sinners refreshes the tired themes about sex that show up in vampire stories again and again, if you’re interested! https://intimatepublics.substack.com/p/sex-in-sinners-a-vampiric-hawk-tuah?utm_source=post-banner&utm_medium=web&utm_campaign=posts-open-in-app&triedRedirect=true