Notes Toward A Critical Barbie Theory

Because I spent four(teen) years prostrate to the higher mind

Now, more than ever, we have to keep talking about Barbie. The film became not just a phenomena, but etched itself into cinematic and feminist history this weekend when it managed to pull in more money than any other film directed by a woman by Saturday night —$377 million overall. It also beat the hell out of Oppenheimer, raking in more than double box office earnings.

It’s always important to notice the direction money flows in for what it tells us about our cultural and political moment, but it’s even more important to notice when that money appears to be supporting the espousal of supposedly radical viewpoints. In the case of Gerwig’s Barbie: Feminism writ large.

At exactly the point that the mainstream adopts an ideology, that ideology becomes consumable. The very belief you upheld to resist fill-in-the-blank [misogyny, capital-P Patriarchy, capitalism] will be repackaged and sold back to you as supportive of your own belief systems. Barbies, it isn’t that the revolution will not be televised (if they can put ad placements and commercials or an anchor’s commentary in the revolution, it will 100% be on Hulu), it’s that it’s not a revolution if it is televised.

The very belief you upheld to resist fill-in-the-blank [misogyny, capital-P patriarchy, capitalism] will now be repackaged and sold back to you as supportive of your own belief systems. Barbies, it isn’t that the revolution will not be televised (if they can put ad placements and commercials or an anchor’s commentary in the revolution, it will 100% be on Hulu), it’s that it’s not a revolution if it is televised.

And yet — for opening night of Barbie, I dressed up in a rollerblade costume ordered online and attended my local indie theatre’s screening of the movie, complete with an indie-made Barbie doll box for photo ops. Also, I ordered neon green hoop earring that are an exact replica of those worn by Barbie, had fake lashes professionally applied, and spent forty-five minutes practicing a YouTube tutorial that taught me how to use two hairbands and a bunch of twisting to achieve the Barbie ponytail.

I feel like it’s important to get it out there that I’m part of Big Barbie! I loved it — strangers took photos with me, the box office guy recognized me from fifteen feet away and handed me my ticket as if my life were as seamlessly choreographed as Barbie’s own. It was awesome. And I loved the experience of watching the movie. It was genuine fun — which is both important and complex. I think the pure playfulness of this movie is significant. As a former theatre kid and, later, while studying critical theories of trauma in PhD school, I’ve thought a lot about that word: “play.” My favorite definition of it is pretty informal and comes loosely from work by Bessel van der Kolk that defines play as thought removed from time. The Barbie movie did exactly for me as an adult what the doll did for me as a child — she restructured the rate and rhythm at which I receive my life and lifted me out of it for a while. Experiences like that are of profound psychological and spiritual value. But on the other hand, there is always a political dimension to fun (take a look at “There Is No ‘Choice’ in Wellness Culture” by Charlie Squire for more on that.)

So, to quote the film’s own ad copy, whether you love Barbie or hate Barbie, you should be thinking hard about Barbie. Here are a few pieces that do just that.

To begin with a Works Cited Page, here is Evan Ross Katz at Shut Up Evan: The Newsletter with The BARBIE Reviews Are In. Katz has compiled key quotes from all the major outlet’s reviews of Barbie. It’s interesting to look at these all side-by-side to note consensus (the movie is stylish and zany) and dissent (a few critics note the conclusion is forced). It’s also interesting to note what discussions aren’t happening that seem like they should be in every review — for example, only Time Magazine approaches the fact that Mattel funded this project or acknowledges Ken’s incel adjacency. This pull from the Time review actually seems to assume an understanding of how the Barbie movie was funded that few viewers actually possess:

The question we’re supposed to ask, as our jaws hang open, is “How did the Mattel pooh-bahs let these jokes through?” But those real-life execs, counting their doubloons in advance, know that showing what good sports they are will help rather than hinder them. They’re on team Barbie, after all! And they already have a long list of toy-and-movie tie-ins on the drawing board. Meanwhile, we’re left with Barbie the movie, a mosaic of many shiny bits of cleverness with not that much to say.

And I have to mention The New York Times review because it irritated me so much with the following line:

Gerwig does much within the material’s inherently commercial parameters, though it isn’t until the finale that you see the Barbie that could have been. Gerwig’s talents are one of this movie’s pleasures, and I expect that they’ll be wholly on display in her next one — I just hope that this time it will be a house of her own wildest dreams.

My generous interpretation of this reviewer’s suggestion that Gerwig’s talents have not yet been “wholly on display” is that they haven’t been on display with such a huge amount of studio cash behind them. But I also can’t help but read this as the remark of a reviewer who can’t conceive of the idea that Gerwig’s smaller, more intimate, and much more “radical” films about female friendship, Frances Ha and Lady Bird, are the filmmaker’s “wildest dreams.”

After you’ve surveyed the critical landscape, read Mattel, Malibu Stacy, and the Dialectics of the Barbie Polemic by Charlie Squire at Evil Female. This is an excellent piece that explores the real trick of this movie: while Gerwig and Mattel are distracting us with the supposedly progressive gender politics of Barbie, they’re actually programming us to be capitalists.

The 2023 Barbie film is a commercial. I’m sure it will be fun, funny, delightful, and engaging. I will watch it, and I’ll probably even dress up to go to the theater. Barbie is also a film made by Mattel using their intellectual property to promote their brand. Not only is there no large public criticism of this reality, there seems to be no spoken awareness of it at all. I’m sure most people know that Barbie is a brand, and most people are smart enough to know this and enjoy the film without immediately driving to Target to buy a new Barbie doll. After all, advertising is everywhere, and in our media landscape of dubiously disclosed User Generated Content and advertorials, at least Barbie is transparently related to its creator. But to passively accept this reality is to celebrate not women or icons or auteurs, but corporations and the idea of advertising itself. Public discourse around Barbie does not re-contextualize the toy or the brand, but in fact serves the actual, higher purpose of Barbie™: to teach us to love branding, marketing, and being consumers.

Next, Jesica DeFino at The Unpublishable interrogates the insidiousness of Barbie’s messaging on beauty standards, pointing out that the film’s inclusiveness really only serves to include and subject a more diverse range of people to western/industrialized beauty standards. Which, ultimately, means more people buying more stuff to achieve those standards. Here’s a great passage in DeFino’s piece, Barbie Has Cellulite (But You Don't Have To):

“We don’t consider the gender gap in time and money spent on beauty,” Dr. Renee Engeln, a professor of psychology, writes in her book Beauty Sick. “But time and money matter. They’re essential sources of power and influence and also major sources of freedom.”

Legally, socially, and psychologically, the message was clear: Women were allowed access to economic power on the condition that they exert that power over their own bodies. “Beauty work” became the silent second job of working women everywhere — not a force for liberation, but a limit placed on it. A negotiation of women’s continued oppression. A concession. Barbie was part of this. She taught young girls they could be anything they wanted to be — astronaut! business woman! President of the United States! — so long as they met the baseline standard of beauty first.

In conclusion, Greta Gerwig is my favorite filmmaker and actually has been since I saw Frances Ha in 2013. I was even more excited than I thought possible to be about her take on Barbie when I read this quote in her interview with The Gentlewoman prior to the film’s release,

I think it’s Walter Benjamin who said that there’s no tool without blood on it. I think kind of anything you look at, you’re going to have the side of it that has something that makes you question it. Certainly. Barbie, just like anything that exists that’s a human creation, it’s got some stuff that’s not so perfect about it.

In the words of Ken:

Gerwig is citing the guy who developed theories of auratic perception, aestheticization of politics, and dialectical image? Could not be more perfect for Barbie!! But after actually seeing the film, I have to say that if we’re going to talk about tools, it’s impossible not to talk about of Audre Lord’s foundational “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House.” In short, Lorde is saying here that the tools of oppression cannot be used to dismantle the logic of said oppression. To be specific to Barbie: you can’t dismantle “patriarchy” while use the primary tool used to uphold it, capitalism.

Spoiler: This failure is most evident in Gerwig’s vision for Barbieland’s final utopia in which the Kens are allowed to return after their patriarchal uprising, but only in subservient positions. They cannot, for example, serve on the Supreme Court until they “work their way up” just like women in the Real World have “had to do for so long.” A logic that insists we all be subjected to the same oppression in the name of “fairness” is not utopic. In fact, it’s kinda Republican — I can’t help but hear arguments about why everyone should have to pay back their student loans because some people already did.

A logic that insists we all be subjected to the same oppression in the name of “fairness” is not utopic.

And speaking of the Supreme Court — I found an ending that suggests any utopia at all is possible in our current moment distressing. The final, hilarious, moment of this film finds Barbie euphorically requesting to see her gynecologist. While I think this is a brilliant bit of writing — crafting a truly surprising and funny final joke for a movie that is non-stop jokes is miraculous — it’s impossible not to be reminded women live in the least utopic America since 1973 as specifically relates to reproductive freedom.

So being at the gyno in 2023 might make Barbie “Real,” but it sure doesn’t make her free.

So being at the gyno in 2023 might make Barbie “Real,” but it sure doesn’t make her free.

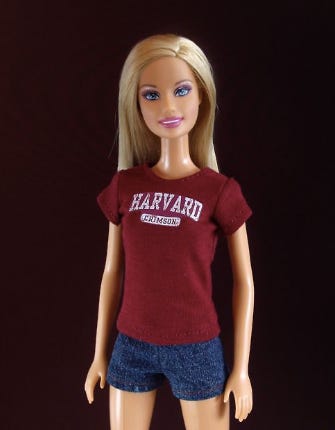

Your camp rec this week: Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story. This is Todd Haynes first film, famously banned, but you can watch a Spanish dubbed version on YouTube. Haynes intercuts documentary footage with Barbie doll actors to explore Carpenter’s life and eating disorder.

Post paywall, a clip to the moment in Frances Ha that I theorize planted the seed from which the Barbie script grew and, yeah, I’ll show you my Barbie (and Oppenheimer!) outfits.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Bimbo Summit: A Pop Culture Study to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.