For the last year, I’ve been thinking about a post

wrote about the hollow horror of last summer’s Longlegs. In particular, this passage:What are you afraid of? When I was a kid, both the idea of heaven and hell freaked me out. Hell for obvious reasons, “torture,” although I didn’t really know what that meant. Sounded bad. But heaven, too, for the whole “eternity” thing. I would try to picture it, something that never ended, and I would fall into panic. What if I got bored? What if I didn’t like it? And then there wouldn’t even be the sweet promise of death to release me from my state because I would already be dead. I think I remember telling my mother when I was around five that I would prefer neither one after I died, thank you. I just wanted things to end.

It’s a small but pretty devastating articulation of spiritual claustrophobia—of the fear not just of punishment but of divine permanence. It makes me think of the single most terrifying experience I’ve ever had with a piece of art. I was sixteen or so and my parents too me to see The Weir (1997) at Steppenwolf Theatre in Chicago. The play is set in a rural Irish pub where a group of locals swap ghost stories to impress a newcomer, a thirty-ish woman named Valerie. One particular ghost story about a pedophile whose dying wish is to be buried with a recently deceased child deeply disturbed me. I quite actually lost sleep over it. The situation was so extreme that my mom sat me down and asked me what was going on one day after school. I’m pretty sure she thought I was hiding some kind of abuse or something, because she was visibly relieved when I told her I was just scared of that story in The Weir.

The solution? She went to the church where I was baptized and filled up a bottle with Holy Water. And you know what? It worked. That’s how convinced I was on both a cognitive and psychic level that spiritual intervention was a real, active force in the world.

In Crispin’s piece, she reflects on how religious horror doesn’t scare her anymore—not because it’s no longer frightening in theory, but because most contemporary depictions are too hollow to touch that raw nerve. As she puts it, no one involved in these films seems to actually fear God. They’re invoking old iconography—nuns, crucifixes, demons—without any real sense of spiritual consequence. And without consequence, there’s no true transgression.

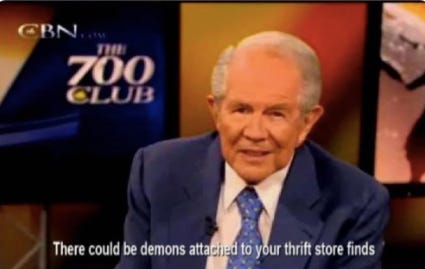

As a kid raised in the Catholic church who stayed terrified of a “real life depiction” of a demon walking up the steps on and episode of The 700 Club (a real IYKY), I totally resonate with Crispin. The hair raising terror that came from watching anything with an exorcism in it left me as soon as I became an adult and stopped intellectually and spiritually believing in the church’s teachings. That said—while I feel discomfort but not fear when I watch, say, The Conjuring, I can still very much be got by a documentary or reality show featuring footage of a person who believes themselves to be possessed. Or, at least claims they do.

A couple weeks ago, I started watching Devil in the Family: The Fall of Ruby Franke, a three-part Hulu docuseries that depicts the transformation of Ruby Franke from a popular family vlogger to a convicted child abuser. The series utilizes over a thousand hours of previously unseen footage from the Franke family's YouTube channel, 8 Passengers, and features in-depth interviews with Franke's estranged husband and their two eldest children. It also includes footage of Jodi Hildebrandt (Ruby’s spiritual counselor and business partner) in the violent throws of a demonic possession that compels her to growl phrases such as, “She’s mine.” I get chills even remembering it. I ended up watching the docuseries way past my bed time, eventually turning off the show mid-possession scene and going to bed scared as a little kid.

The Secret Lives of Mormon Wives doesn’t offer such a visceral terror, but the religious consequences are clear and present. The spiritual horror here isn’t aesthetic—it’s embedded. The terror isn’t in Satanic ritual or hellfire. It’s in obedience. In being watched not just by your husband, your bishop, or your followers—but by God. My childhood fear of eternity, of being stuck in a divine system I didn’t choose, came rushing back as I watched women try to reconfigure their lives without ever letting go of the belief that submission might still be sacred. There is in fact one scene in which a divorced woman marvels in a disassociated manner at the fact that she is still bound to her ex-husband because they were married in the temple, a scared covenant that means that you remain married in the afterlife, even if you and your ex-husband fucking hate each other.

I think the real reason we can’t look away from Mormon MomTok is not because it’s glossy or aspirational. Many critics claim the popularity of the show is simply due to the public’s interest in seeing hot young women fight over stupid shit, but, frankly, there are a million shows you can see that on. I think we’re actually watching because it’s unsettling in a way that, say, The Real Housewives of Salt Lake City (another show featuring Mormon wives, one of whom actually used to be married to one of the Secret Lives Wives’ husbands) is not. The matching family outfits, performative soda orders, and confessional TikToks filmed in spotless SUVs aren’t just lifestyle choices made to catch the eye of TikTok viewers. They’re part of a theology, which is actually what makes this show so fascinating.

Plenty has been written about the rise of Mormon momfluencers and their uncanny knack for turning domesticity into spectacle.

Lenz’ recent piece, Watching women cannibalize themselves for fun and profit: The second season of The Secret Lives of Mormon Wives identifies the exhaustion and entrapment at the heart of these women’s carefully curated lives, reading them as avatars of a broader American female experience: overworked, under-supported, and trapped in patriarchal systems that demand performance as the price of survival. I agree entirely with Lenz’s argument that the show had resonated so powerfully because it mirrors how patriarchy shapes all our lives. “It’s harder to say, ‘Oh, that’s just the Mormons,’” she writes, “when so many of the show’s themes hit close to home.” While that’s true, I think analysis of this show that focus on the patriarchal structure of these women’s lives without also taking the seriousness of their faith into account are missing an important element: the spiritual scaffolding that makes these roles feel not just inevitable, but divine.When a Mormon wife gets on TikTok to show her cleaning routine, she’s not just sharing tips—she’s bearing witness. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints teaches that the home is a sacred space, a site of spiritual labor. Domesticity isn’t just work; it’s worship. And Mormon momfluencers are streaming that worship live.

Which brings us back to Ruby Franke. When she was arrested in 2023 for child abuse, it wasn’t just a scandal, it was a theological rupture. Franke’s brand had always been about alignment: with her husband, her faith, her God. Her downfall exposed what happens when submission, authority, and righteousness blur into control. The aesthetic of Mormon femininity—clean, smiling, compliant—disguise a deeper submission to spiritual authority. And when that authority is patriarchal, unaccountable, and sacralized, it becomes almost impossible for these women to critique without appearing to blaspheme. I think it’s important to keep sight of the fact that these women aren’t just wives or influencers, nor do they view themselves as such. Rather, they see their first responsibility in life as missionaries of a soft-power theology that teaches women to find agency in submission, to monetize their own marginalization, and to perform obedience as a path to exaltation.

What sets The Secret Lives apart from Ruby Franke or most other Mormon Momfluencers is that they think they’re using their platforms to question the very structures they appear to uphold. Taylor Frankie Paul has said explicitly (and repeatedly throughout season two) that the point of the show is to highlight the diversity of lived Mormon experience:

There’s this stigma that all Mormons are supposed to live the same way or do life the same way. The point of our show is that there are so many different ways of living Mormonism. It’s a spectrum.

That spectrum includes breadwinner wives who fund their families with brand deals and affiliate links, like Mayci Neeley launching a prenatal supplement line or Whitney Leavitt securing a $20,000 vibrator sponsorship. The women don’t just permit taboo topics like sex and surgery—they host paint-and-sip nights themed around labiaplasty and orgasm, complete with mocktails named "the pink pussy" and "labia-licious." These aren’t just jokes—they’re micro-sermons. Reframing sexual pleasure as spiritually permissible, even vital, is one of the most radical acts a woman can perform within a religion that demands submission in bed as well as in life.

This is what makes The Secret Lives of Mormon Wives such an unsettling watch: it’s not a rejection of Mormonism, it’s a reformation happening in real time. The content is doing theological work—grappling with sin, sacrifice, and sanctity through the visual language of influencer culture. When a woman confesses she never had an orgasm in her marriage, she’s not just breaking a taboo—she’s asking a doctrinal question: what does it mean to be fulfilled in a system that treats your pleasure as irrelevant?

These are micro-reformations happening in algorithmic fragments. But even this reformist edge is complicated by capitalism. The more a woman speaks out, the more views she gets. The more she confesses, the more she commodifies her resistance. And the platform rewards it—until it doesn’t. Unless, of course, she goes too far, usually by threatening not just her marriage or her brand, but the spiritual logic that underpins both.

I think that’s why I find this content so eerie. It’s not just reality TV or influencer culture, it’s an actual televised faith crisis. Women broadcasting their inner schisms while smiling through teeth whiteners, meanwhile their theology is coming apart in public.

The Secret Lives of Mormon Wives is so compelling—and so disturbing—because it isn’t just about the gender politics. It’s about the sacredness of the role itself. When you believe God wants you to be a certain kind of wife, mother, or daughter, submission doesn’t feel like a trap. It actually feels like transcendence. On the other end of the spectrum? Outer darkness. Total and eternal existential collapse.

For me, that’s what makes this particular strain of (what I’m calling) religious horror feel so real. Jessa Crispin was right that iconography doesn’t scare us anymore, precisely because it’s so often emptied of consequence. But in TSLMW, the stakes are spiritual and personal and eternal. These women aren’t dressing up as nuns or playing with crucifixes. They’re trying to please God, raise children, and survive marriage within a framework that insists salvation lies in obedience.

I have a lot of hope that the mainstream success Taylor Frankie Paul is experiencing will continue to embolden her, and maybe even make it financially feasible for her to distance herself from the Church. It’s clear from her confessionals—which often land with the raw energy of someone publicly thinking through a theological break—that she’s seen the deep flaws patriarchy had embedded in the system. But it’s also worth saying that she’s still a member of the Church. Unlike some of the wives on Real Housewives of Salt Lake City, she hasn’t left or been excommunicated for her divorce or swinging scandal. If she does stay, I don’t think it will be because of MomTok or brand deals. She’s got 5.1 million followers on TikTok, conveying that her appeal has passed out of a niche Mormon momfluencer orbit to full blown mainstream success. No, I think if Paul stays, it will be because of something harder to dismiss: a spiritual obligation.

That said…Paul has taken the “Mormon” part off her TikTok and Instagram bios, so fingers crossed for some truly shocking (and validating) twists in the second half of season two.

i watched one episode and my main takeaway was everything is ugly. their big boring beige houses are ugly, the cities are ugly, the restaurants are ugly, everything looks dead and interchangeable. they wander around like sims from one to the other with very little difference between any of the spaces they are in and very little difference between each other and how they all look-- like ginger bread men baked in an oven all cut from the same shape. to me that seems like being trapped in an endless hell. it made me feel anxious and itchy