We've Already Met the Main Character.

Nicole Kidman, Babygirl, and the postmodern career arc of the legacy actress

I would love it if you shared or stacked a quote from this if you like it!

Sometimes I wonder if I care a lot more about Nicole Kidman than most people. Maybe that’s because she shot her first film the year I was born. This is a fact I only recently learned, while researching for this very essay, but maybe it explains why I didn’t grow up watching her the way I’ve watched other stars. This is probably heightened by the fact that, unlike other stars (Elisabeth Shue and Sarah Jessica Parker also debuted in 1983), Kidman’s career has never really taken a pause. She’s never had a comeback because…she never left.

The pervasiveness of Kidman shaped me more than I probably realized. The mother in my novel MONARCH, Grethe, is the only character I’ve ever consciously based on a real person—and that person was Nicole Kidman. Grethe sleeps in a cryochamber to preserve her youth, a literalization of something I’ve always felt watching Kidman onscreen: that she exists outside of time. Not just in the figurative sense, as a capital-S Star who survives the churn of trend cycles and platform shifts, but in the literal sense too—her famously unlined face, the surgically enhanced perfection of it, the visible effort it takes to remain iconic. The preservation becomes part of the performance.

In a way, Kidman’s roles matured as I did—moving from ingénue to spectacle to something stranger and harder to categorize. She was always ahead of me, at least aspirationally. That’s part of why Babygirl hit me the way it did (I wrote about it how critics were getting this movie wrong the week it was released nationally). Directed by Halina Reijn, the film doesn’t just cast Kidman—it casts her history. Reijn has said she chose Kidman specifically to give her Eyes Wide Shut character the agency she was never granted in that film. Reijn explains,

We don't even know what [Alice is] going through. We're totally in his mind, heart, and soul. I want to know, 'What if she would've gone and actually would've lived her fantasy?' That's what this is — my answer, playfully and humbly, to the male Eyes Wide Shut.... All of us women are ready and hungry to see and hear stories about how we feel and from our perspective.

And Babygirl runs with this idea—not just revisiting but rewriting, as if all the intervening decades were building toward this kind of feminist revisionism. As if the act of watching Nicole Kidman —still— isn't just nostalgic, but transformative.

Watching Kidman now isn’t just an act of fandom. It’s an encounter with cultural memory, with everything she’s been made to mean.

In Stars, Richard Dyer explains that a star is both what she seems to be and what she is, a contradiction that makes her image not just consumable but ideological. Kidman’s image has always existed in that tension—between artifice and authenticity, desire and detachment. Babygirl doesn’t resolve that contradiction; it magnifies it. Star theory has long told us that stars are texts—composites of performance, persona, publicity, and audience desire. But what happens when the text fights back? What happens when a star not only endures decades of contradictory meaning but begins to revise it herself?

Kidman has always trafficked in this kind of instability. While many of her films could be studied for the way in which they dialogue with Babygirl, I think To Die For, Eyes Wide Shut, and The Paperboy are the most relevant to the themes of power, sexuality, taboo, and desire that Reijn explores in Babygirl.

In To Die For (1995), she plays Suzanne Stone, a woman who murders her husband for the chance to read the weather. It’s satire, yes—but it’s also the blueprint for the influencer era: a woman whose ambition is dismissed as narcissism, whose image is both weapon and trap.

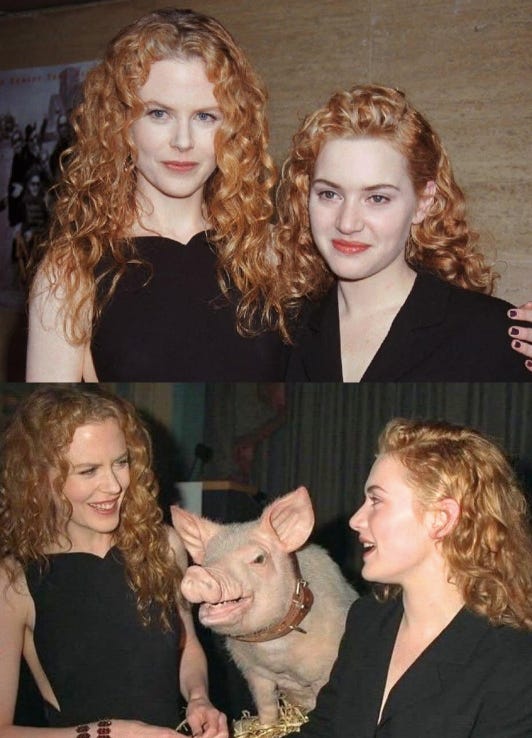

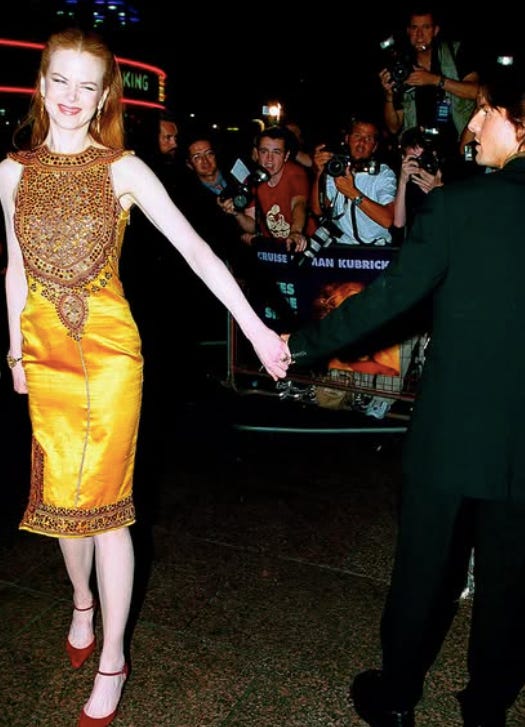

In Eyes Wide Shut (1999), Kubrick’s cast real-life on-the-rocks couples Kidman and Cruise. Their casting as Alice and Bill Harford seemed like tabloid fodder: Hollywood’s golden couple starring in a movie about sexual fantasy and betrayal. Kubrick, famous manipulator of actors, deliberately blurred the lines between their on- and off-screen roles, prolonging the shoot for over a year. In a 2024 interview, Kidman admitted, “I would have stayed a third year... Does that mean I’m crazy?” Maybe, girl! But I’m glad you stuck it out because Eyes Wide Shut is a masterpiece.

Especially considering the deeper resonance of Kubrick’s casting: at the time, Kidman and Cruise were immersed in Scientology (Cruise, of course, still is. Kidman credits her psychologist parents for giving her the critical and emotional faculties to get out). Eyes Wide Shut—with its elite sex cults, masks, and ritualized performances—feels less like fantasy and more like exorcism with this knowledge. Knowing that Kidman would eventually leave both Cruise and the Church retroactively sharpens her performance. What once read as unreadable now feels encrypted. Babygirl doesn’t just decode it—it lets her speak. It’s feminist revisionism at the level of casting.

It takes another thirteen years and a number of star turns (Moulin Rouge! and The Hours, in particular) before Kidman returns to her decidedly unseemly roots with The Paperboy (2012). Co-starring Zac Efron, she plays Charlotte Bless, a hyper-sexualized death-row devotee whose eroticism is so excessive it becomes defiant. The infamous urination scene reads less as shock than reclamation. It’s not that she doesn’t care what we think; it’s that she’s daring us to keep watching. This is one of those films that was famously booed at Cannes (others on this list? L’avventura and Dancer in the Dark, to name just two). The Alliance of Women Film Journalists even voted Kidman the actress “most in need of a new agent” after this film came out.

But that’s part of the brilliance of Halina Reijn’s casting. Audiences know Kidman won’t shy away from eroticism or cringe. Her reputation brings an element of chance to her performances that you don’t get from any of her contemporaries (I’m looking at Sandra Bullock and Gwyneth Paltrow, although not you, Naomi Watts!). She’s unpredictable in a way that feels both theatrical and deeply personal — like watching someone mid-transformation.

It’s no surprise, then, that her presence in Babygirl has spilled beyond the screen. Since the film’s premiere, Getty Images of Kidman on the red carpet have gone viral—not because they’re glamorous (though they are), but because they feel canonized. Also, perhaps, because there are 89,785 of them (at the time of this writing, anyway). Each one reads like a still from a movie that hasn’t been made yet.

Actually, this isn’t new: audiences have always tried to narrativize her image, even when they get it wrong. Take that famous shot of her mid-scream, which circulated for years as a triumphant post-divorce moment—“Nicole Kidman leaving her lawyer’s office after signing the papers.”

Kidman has since claimed this was a still from a movie (although what movie, she didn’t say. Neither costume nor hair correlate with anything she was filming at the time…). But the “fiction” stuck, maybe because it felt truer than the truth. The audience doesn’t just receive the image anymore—it activates it, recontextualizes it, memes it, archives it. And Kidman, impossibly, remains legible across every iteration.

This is the aesthetic politics of the legacy actress: not just being remembered, but being re-activated, re-deployed, and made strange again.

We live in a moment where cinema history is no longer linear—it’s lateral, recursive, crowdsourced. Every image of Nicole Kidman now circulates alongside a thousand others: Practical Magic gifs, Big Little Lies edits, TikToks of her AMC ad, fan theories about her appearing barefoot at Cannes. Her star image is no longer a singular text—it’s a palimpsest. A lieu de mémoire, to borrow French memory theorist Pierre Nora’s term: a site where memory crystallizes and secretes itself, not because the memory is stable, but because it is constantly being reactivated. Kidman’s career functions in this way—not as a stable object of nostalgia, but as a living, volatile archive that absorbs and refracts culture.

That’s what Babygirl understands so well. It’s not just about one performance, one character, or even one revision. It’s about making a space for all of them to exist at once. Kidman the ingenue, the tabloid wife, the indie darling, the meme, the muse. Hers is a postmodern career arc—fragmented, nonlinear, reflexive, always aware of its own construction. She becomes the surface on which the culture writes and overwrites itself.

So, yeah, maybe I care more about Nicole Kidman than other people do. Or maybe the archive is eating itself.

We live in a moment where cinema history is not only longer, but more accessible and user-driven than ever before. The audience archive is infinite: Letterboxd reviews, Twitter threads, YouTube essays, TikTok fan edits. Star images don’t just persist—they mutate. A 1995 Kidman becomes a 2012 Kidman becomes a 2024 Kidman becomes a meme becomes an auteur’s obsession becomes a scene that finally gives her character a voice. This isn’t just nostalgia—it’s re-authorship.

And so it makes sense that Reijn’s project would be to revise rather than reference. To build forward from the unresolved. What if Alice Harford from Eyes Wide Shut had left her husband, raised her daughter, and become someone else entirely? What if the story that was once about a man’s descent into desire became one about a woman’s re-entry into herself?

Maybe I care more about Nicole Kidman because I’ve been watching her my whole life. Or maybe I care because, like the best stars, she reminds me that a performance is never really finished. It’s just waiting for its next version. Like, well, all of us.

There is something true about following an actor who sticks to your attention from your youth. You mentioned Sarah Jessica Parker, I've been following her since Annie on Broadway. Seeing her go from stage to tv (Square Pegs is a masterpiece and Carrie Bradshaw's true origin story) to film was watching a star being minted in real time.

I feel this way about Kirsten Dunst! Also having just watched Baby Girl, that is fascinating that it was written as a response to Eyes Wide Shut-- I absolutely love that