Of course I owned a delicate gold nameplate necklace that read “Candie” in the early aughts. I was 14 when Sex and the City started and 20 when it ended, but Carrie’s Post-it note breakups and Samantha’s attempts to feed her partner a wheat grass shot that would make his “spunk” (Samantha’s words) more palatable fell somewhere between too mature and too low brow for teenage me — I didn’t get, and furthermore, I didn’t want to.

But still, I had to have the nameplate necklace, which I special ordered because while you can find lots of “Candy”s and some “Kandee”s, you cannot find a “Candie.” (Another moment where I wonder if my mom thinks things all the way through — not because the spelling isn’t traditional, but because as I liked to morbidly point out in elementary school, it is basically Can die.) I wanted the necklace because I was —I’ll say it!— the most fashionable person in my high school, which was, frankly, often alienating. But I was also painfully shy. Really — the kid whose locker was next to mine thought I was a foreign exchange student for almost an entire year because I never spoke. I was thinking about this relationship between introversion and presentation when I read Anne Helen Petersen’s recent post, “The Thread Vibes Are Off”:

People think Instagram is for extroverts, for people who want to broadcast every bit of their lives, but most Instagram users I know are shy — at least with public words. Instagram is where parents post pictures of their kids with the caption “these guys right here” or a picture of their dog with “a very good boy.” The text doesn’t matter; the photo speaks loudest.

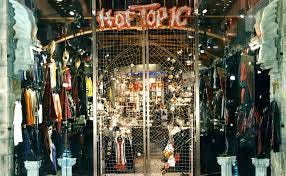

Petersen is comparing social media platforms here, but this resonated with me as a way to describe my high school presentation — a mix of Cher Horowitz, Marilyn Monroe, and a sentient Hot Topic mannequin. I had not just Taste, but researched and contemporary refs — in 2000, I couldn’t have told you who Mr. Big was, but I sure as hell knew Patricia Field. Hence the absolute requirement of a nameplate necklace.

So I started this week’s newsletter with the intention of writing about the way nostalgia functions to transform objects into camp. Of this subject, Sontag writes:

…the process of aging or deterioration provides the necessary detachment — or arouses a necessary sympathy. When the theme is important, and contemporary, the failure of a work of art may make us indignant. Time can change that. Time liberates the work of art from moral relevance, delivering it over to the Camp sensibility.

My intention wasn’t to suggest nameplate necklaces have been transformed into Camp objects in the era between Sex and the City and And Just Like That, but to think about the way And Just Like That’s presentation and obsession with Sarah Jessica Parker’s “embrace” of aging is itself campy. (Do you have the stomach to read even more AJLT content? Let me know in comments if you want to hear about SJP’s non-facelift and camp culture.)

At any rate — this led me to “Say My Name: Nameplate Jewelry and the Politics of Taste” by Isabel Flower and Marcel Rosa-Salas, an intensely interesting and well-written academic article that utterly derailed all of my original plans for this week’s post.

Flower and Rosa-Salas consider nameplate jewelry as a staple of hip-hop culture and cinema, which ultimately functions as an aesthetic gesture intended to combat social alienation and create “excess flesh” and sartorial articulation. Flower and Rosa-Salas look into

…the nameplate’s genesis in mass American culture [to examine] how the discourse surrounding the style’s ostensible “tackiness” is rooted in notions of taste and aesthetics that are shaped by hierarchical race, class and gender politics.

They think through the nameplate necklace as a symbolically political object that:

…engages directly with the practice of naming. It declares selfhood and individuality through legibility. Perhaps the first concern for the nameplate is readability…The nameplate’s locus in the written word engages concerns about literacy, naming as a civic right, and the politics of recognition.

Additionally, they track Carrie Bradshaw’s relationship with the accessory, which stylist Fields explained to InStyle in 2015,

I have a shop in New York City, and a lot of the kids in the neighborhood wore them [blingy monogram pieces]… I thought, ‘Maybe I’ll show it to Sarah Jessica and she’ll like the idea.’ She did, and she made it happen. It became a universal, long-lasting thing.

Flower and Rosa-Salas note the way Carrie’s signature piece (an item described by Variety as “a talisman of sorts during Carrie’s most tumultuous moments.”) is actually “symbolic[ally] and sartorial[ly]” insignificant to her in Episode 12 (“Just Say Yes”). This is the ep in which Miranda helps Aiden select an engagement ring for Carrie, which results in the following conversation:

CARRIE: The ring was not good. It was a pear-shaped diamond with a gold band. It’s just not me.

MIRANDA: But you wear gold jewelry?

CARRIE: Yeah but like—ghetto gold for fun. This is my engagement ring.

The And Just Like That reboot of SATC has attempted to avoid this kind of blatant racism and classism assiduously — Rachel Cook at The New Statesmen calls the show’s “combination of glib identity politics and extreme shopping” a “woke horror show.” And yet — the necklace is still there, and it’s still a big fucking deal. In fact, in Episode 3 of the current season, “Chapter Three,” Carrie bargains with a mugger to allow her to keep the necklace.

While I do think that the cultural appropriation of the nameplate necklace is a bit of an idiotic contrast to the show’s lazy side plots about racism, I’m not asking why AJLT hasn’t updated this facet of Carrie’s style. The fact is that the creators of this show are not genuinely interested in creating a more sensitive or educated Carrie Bradshaw. The character is, in fact, exponential more privileged than the oven-shoe-storage version of herself she was when Aiden presented her with the offensive pear cut ring. We watch this woman walk off a job and refer to it as a great way to free up time.

The plot of “Chapter Three” is in fact that Carrie is being targeted to donate cash to a new media outlet, but she thinks she’s being asked to write for it. She is so utterly out of touch that she hasn’t even noticed her social identity has shifted from writer to wealthy widow.

So, no, I won’t bother to interrogate choices that are so ingrained in the fabric of this show as to be non-existent to its creators. But I do wonder: if nameplate necklaces represent citizenship for oppressed groups, then why does Carrie Bradshaw need one — especially now that, as the show points out, her “pockets are considerably deeper”? Again, I turn to Flower and Rosa-Salas, who write:

The character of Carrie Bradshaw did not make the nameplate “a universal and long-lasting thing” — what she did was to sanitize and situate it within dominant taste, removing its legacy, cultural history, and political valence, and designating it as a product fit for mainstream consumption. Carrie, as an upper-middle–class white woman, acted as a proxy for a marketable fantasy of America.

I believe that for the show’s creators, the nameplate necklace represents the more free-spirited, innovative style choices that Carrie Bradshaw was supposed to represent when SATC began. The character was once a scrappy writer new to the City, her most public mode of expression her fashion choices, which were fun, studied, unconventional and yet conventionally attractive. Of course Carrie has always been mainstream, but there was a true artistry and articulation to the combination of eras, styles, and price points she combined. In fact, one of the show’s most famous lines encapsulates the character’s relationship with fashion and the city,

When I first moved to New York and I was totally broke, sometimes I would buy Vogue instead of dinner. It fed me more.

Taste was once important to this show — in fact, it was the show. It assigned meaning and sustenance.

Style over substance, always.

But now Carrie Bradshaw, ever substantive, has more means the ever and the nameplate necklace serves as a quaint and nostalgic talisman of the OG SATC era. If, as Sontag writes, “Intelligence is really a kind of taste: a taste in ideas” then, just like that— Carrie Bradshaw might be all out of new ones.

So what’s my Camp rec this week? Evan Ross Katz Instagram, which is a living archive of the Campiest things happening on screen. Sontag writes:

Camp is a kind of love, love for human nature. It relishes, rather than judges, the little triumphs and awkward intensities of “character.” Camp is a tender feeling.

There’s currently nowhere on the Internet where I feel that specifically tender feeling more than a scroll through Katz’s page. To see my most messaged memes from this account and get a surge of dopamine, go behind the paywall.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Bimbo Summit: A Pop Culture Study to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.